Nonstop over water is a big deal. In the early days of aviation, planes failed frequently, and forced landings were standard procedure. Landing in a cow pasture was problematical. Landing in the ocean would likely be fatal.

In 1909, Louis Bleriot flew nonstop (there wasn’t any other way to do it but nonstop) across the English Channel. He would certainly have set off a round of longer and longer first flights, but WW I got in the way.

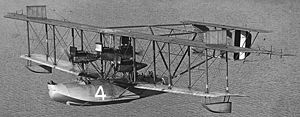

After WW I, there was a surplus of newer, more sophisticated aircraft. Two British flyers, John Alcock and Arthur Whitten-Brown, along with several other competing teams, set out to cross the Atlantic nonstop, beginning their flights in Newfoundland. Hawker and Grieve took off first, crashed a thousand miles into the flight, and were picked up by a passing steamer. Raynham and Morgan tried an hour later, but crashed during takeoff.

Alcock and Brown left Newfoundland on June 14, 97 years ago today. Alcock, the pilot, had waited as long as he dared for better weather, but finally decided to chance the near gale force winds. The two aviators, in a single open cockpit, took off at 4:10 PM, barely clearing the trees at the end of the runway. They headed east toward Ireland, with the wind behind them to hurry them along.

Shortly after takeoff, Brown discovered that their wireless was not working. He crawled out of the cockpit onto the wing to get a look at the small propeller mounted under the fuselage which powered the radio. Three of four of the blades had sheered off. They would remain out of communication until their flight either succeeded or failed.

At 7 PM, the exhaust pipe on the starboard motor overheated, split, and burned away. This left the motor running erratically, but there was no way to fix it.

They were flying at 3000 feet; Brown was navigating by sextant. When they entered a fog bank. Alcock had to rise to 12,000 feet so they could see the stars again. About sunrise, they entered an even higher bank of fog. They could not tell left from right or up from down, but the instruments showed the plane listing and then entering a spin. They dropped down, blind, almost to the ocean itself. Fifty feet above the water they cleared the fog and clouds with wings vertical. Alcock pulled up just above the water.

For hours they flew in alternating clouds and clear air, until the storm turned the sky black in front of them. Then they entered snow, sleet, and freezing rain. Alcock tried unsuccessful to fly above the storm, but the only result was that a critical gauge, fixed to a strut outside the cockpit, iced over. Again Brown had to leave the cockpit to chip away the ice, but this time he had to remain, clinging to the cross wires, to repeat the process every time the gauge re-iced.

Eventually they had to drop down through the storm again to see the ocean below so they did not overfly their destination. At 8:15 AM, June 15th, they sighted the Irish coast.

Alcock and Brown were knighted for their efforts, and lionized in Britain.

In America, not so much. Eight years later, Lindbergh flew nonstop from New York to Paris, following the same route overwater as Alcock and Brown, and became famous throughout the world as the “first man to fly the Atlantic”.

***

These posts are necessarily short, so details get missed along the way. Like Bleriot before them, Alcock and Brown, and their competitors, were in pursuit of a monetary prize. This time it was for the first single plane to cross from North America to Britain in under 72 hours. The “single plane” rule was to avoid someone flying from Newfoundland to Iceland, jumping into a second, newly fueled and serviced plane, and completing the trip. Stops along the way were allowed, as long as the same plane was used.

A decade later, Lindbergh was also in a race with a bunch of other flyers to win a monetary prize for the first non-stop flight from New York to Paris. There was nothing in the prize about a solo flight. The other competitors were in larger planes, with crews. Lindbergh flew solo to save the weight of a second person, so he could carry more fuel.

Does this sound familiar? The X-prize, recently won by Burt Rutan’s Space Ship One, was modeled after these early aviation prizes. Even the moon landing was the result of competition, not for money, but for prestige and the military high ground.

If you want more information on early aviation feats, check out Famous First Flights That Changed History, by Lowell Thomas, junior and senior.