I wrote a post some time ago on the subject of No Child Left Behind, without saying one good thing about the program. I know almost nothing about Common Core, since it came on the scene just as I was leaving. When I retired, I retired. I enjoyed my days of teaching, but twenty-seven years was enough.

I wrote a post some time ago on the subject of No Child Left Behind, without saying one good thing about the program. I know almost nothing about Common Core, since it came on the scene just as I was leaving. When I retired, I retired. I enjoyed my days of teaching, but twenty-seven years was enough.

Without reference to the latest nonsense, I can say as a general and probably universal rule that a lot of BS floats down onto teachers from above. And from whom?

Everyone knows the saying, “Those who can, do, and those who can’t, teach.” Like most sayings, it isn’t always true, but sometimes it feels true. There is another saying that only teachers know. “Those who can, do, those who can’t, teach, and those who can’t teach, teach teachers.” Again, not universally true, but I have known some Professors of Education who fit the aphorism with sad precision. And I’ve seen a lot of self-appointed experts who make the circuit of schools, giving training programs they devised themselves, who could spin out reams of self-evident drivel as if they were conveying the word of God.

It makes you wonder. Could it be that they weren’t fitted by their education to work outside of the schools, but they would do anything to get away from kids? I don’t know. I never knew any of them personally. I can tell you that of the hundred or so trainers I endured while teaching, only one or two had anything worthwhile to say.

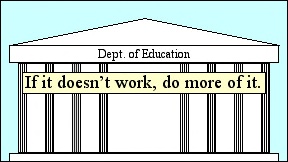

I can also tell you that there should be a banner on the State Board of Education building that reads, “If it doesn’t work, do more of it.” They double down on every bad idea.

________________

The French scholar Jean Piaget, studying children back in the 1930s, discovered that there are stages of readiness for learning. If you try to teach a skill before the readiness is there, it won’t take. I can’t say that is a shocking conclusion. What is shocking is that eighty years later the educational establishment is pretending that it isn’t true.

Everyone can learn. Okay, that’s probably true, but an administrator who says it, means this: Everyone can learn everything. And that’s a lie.

Worse, in their actions, in the textbooks they approve and the tests they give, they are really saying: Everyone can learn everything, and all at the same age, on the schedule we set. And that’s just bullshit.

In California about the time I retired, students in eighth grade had to take algebra, whether they were ready or not, whether they could pass or not — whether they would ever be ready or not. But as soon as they were in ninth grade, and presumably a year more advanced, they could opt out of algebra and take something easier.

Read that three times and it still won’t make sense.

The general rule is this: the state assigns a skill to a certain grade. Some kids get it, some don’t. Does the state let the latter group try when they’re older and more mentally developed? No. They say the students lacked readiness, but they don’t mean readiness in the way Piaget meant it. The state thinks readiness can be taught, so teachers have to try.

If students can’t understand algebra in eighth grade, the schools could teach it to those who are ready, and teach another year of more basic math to the others. Fat chance. Instead the state requires pre-algebra of seventh graders so they will be ready for algebra in eighth. And when that doesn’t work? Let’s try pre-pre-algebra in sixth grade? Where will it end — with expectant mothers sleeping with opened algebra books on their baby bumps?

Read that three times. No, read it 4(2N+3) where N=9 times. It still won’t make sense.

Like it says in the title, get ready for prenatal algebra.

________________

All right, if any of you are young and want to change the world by becoming teachers, more power to you. You are needed.

But first, buy yourself a big pair of hip boots. It’s a swamp out there.