Backstory — these are the things a writer has to know about his fictional universe, most of which will have happened before his actual story begins. Some is dribbled out to the reader as the story progresses. Much is never known to the reader, but remains essential nonetheless.

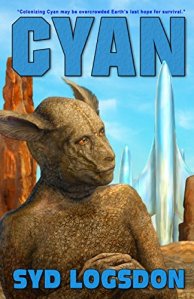

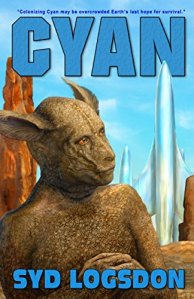

The novel Cyan takes place in the late twenty-first century, but it was written during the last decades of the twentieth and first decades of the twenty-first century. A lot of things changed during those decades, and so did the backstory.

When I started Cyan, the expedition to Procyon was to be mounted by an international body as a cooperative effort. As the story matured in my mind, the notion of cooperation that was so important to the creation of the International Space Station began to fade in the real world. Things got grittier on Real Earth and also on the Earth of the novel.

In that changing backstory, some joker nuked Washington, which ushered in an America First period worse than the Trump era. That wasn’t a prediction. It’s just that the Open Hand and the Closed Fist have alternated throughout American history, and I needed a dystopian, overcrowded Earth to motivate extra-solar exploration.

Cooperation was no longer an option in Cyan; an all-American crew was required. Well, almost all-American, since the new America had gobbled up some of its neighbors as I watched the backstory change.

Due in large part to a disastrous economic downturn in the mid twenty-first century, Canada allowed itself to be swallowed up by the U.S.. Mexico and most of the Caribbean were given no choice. The result was the U.S.N.A., the United States of North America, twice as big with its new capital in Chicago.

Was the downturn due to tariffs? Beats me; all this reorganization of the backstory was finished long before I had ever heard of Trump, and I thought tariffs were a dead issue. After all, they had almost destroyed the American economy during the Jefferson administration, and that was a long time ago,

If this makes Cyan sound depressing, don’t worry. All this has already happened by the time the novel opens. Our ten explorers are half way to Procyon, where none of their problems will be political — at least until their year of exploration is over and they return to Earth.

— << >> —

In the beginning, when the explorers were to be from many countries, I chose their names accordingly. By the time I started reorganizing the backstory, they had already become people to me. I wasn’t going to give up anyone, and I wasn’t going to rename anyone.

Originally Stephan Andrax was Danish, Debra Bruner was American, Petra Crowley was Greek, Keir Delacroix was French, Viki Johanssen was Swedish, Gus Leinhoff was German, Leia Polanyi was from somewhere in the South Pacific, Ramananda and Tasmeen Rao were from India, and Uke Tomiki was Japanese.

Once they all had to be citizens of the U.S.N.A., this might have posed a problem. However, we are a nation of immigrants. Even in 2026, every one of them could have reasonably come from Topeka.

Just for fun — just because I could — and just because it was one of the places I had studied, I chose to let Tasmeen and Ramananda come from Trinidad, the newly admitted seventy-first state.

Yes this is an ongoing advertisement for Cyan,

available from Amazon.