The Space Age Begins

Britain measures eras by the reign of its Kings and Queens. America measures eras by Presidents. In our look at the beginnings of science fiction, we are about to enter the Truman/Eisenhower era, even though neither man will be our focus.

— << >> —

Hiroshima changed everything.

Science fiction people had read Einstein, or had tried to, so they knew about nuclear fission. They knew that an atom bomb could be built, and were expecting it. A few even got in trouble because they used atom bombs in stories, when the FBI was convinced they had it locked into secrecy.

For the rest of the country, Hiroshima was a shock to the heart.

It didn’t take long for the Russians to get the A bomb. Then we got the H bomb. Then the Russians got the H bomb. Welcome to my childhood.

Suddenly the future had become the present. Everybody was still driving ancient looking cars (no cars had been produced during WW II) and dressing like people in the old movies, but their world had been ripped open by futuristic perils.

Literature reacted to the situation. The Saturday Evening Post, that bastion of American norms, broke tradition and published a science fiction short story, The Green Hills of Earth by Robert Heinlein. Colliers Weekly published Wernher von Braun’s article Man Will Conquer Space Soon.

Von Braun also partnered with Disney to produce three episodes of Disneyland (as the Disney TV program was then called). The first, in March of 1955, was called Man in Space. This was followed by Man and the Moon and Mars and Beyond is later seasons. These were humorous and relied heavily on cartoon animation, but they showed American youth what the future held in store.

Eisenhower’s presidency saw a worsening of the Cold War, the rise of ICBM’s to deliver H bombs, and the development of satellites. The push for space flight had been properly begun. NASA was formed in 1958.

Space flight is key to science fiction, but it is by no means the whole of the genre. SF, by its nature, is always out ahead of contemporary science, and the giants of science fiction were producing major works during this period. The main difference from the golden age was that there were more novels, fewer short stories, and people had stopped laughing at the genre.

This was the era of Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End and Issac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy, while Robert Heinlein revised his novella Methuselah’s Children into a full novel.

This era also saw the rise of near future “science fiction”. The quotation marks are there to point out that this wasn’t really science fiction at all, because it was reacting, not predicting. Atomic power, atom bombs, jets, and rockets had been the stock in trade of science fiction fifty years earlier when they did not exist. Now they were the stock in trade of mainstream writers because they did exist.

Fail Safe was probably the most notable of these near future science fiction novels. It began as a short story in 1959 and was revised into a novel that appeared in 1962. In it, an American bomber is mistakenly on route to destroy Moscow with nuclear bombs. The American President, who cannot call back the bomber, must sacrifice millions of American lives to avert a world destroying all out nuclear war.

On the Beach was even more somber. Years after a nuclear war, people of Melbourne, Australia wait for inevitable death as fallout from the northern hemisphere drifts down upon them.

No fun novels for a no fun time.

There were many others. Philip Wylie, who was already an established science fiction writer, turned out Tomorrow and Triumph. I read both in high school.

This new sub-genre of science fiction continued to gain readers who might never have read Clarke or Heinlein. In 1984 it reached apotheosis when Tom Clancy published The Hunt for Red October.

— << >> —

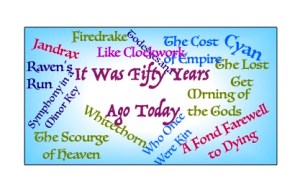

Over the course of this blog, fifty year anniversaries of events from the early space program kept happening, and I kept writing about them. By the time of my covid hiatus, those posts had grown into a book to be called Brief but Glorious.

Of all the books I plan to e-publish, it is the most dubious. Not the text — that’s fine — but I want to illustrate it heavily with NASA photos, and I don’t know what kind of technical problems that will cause. I have tentatively scheduled it for October 2027, but that could change. I’ll keep you posted.

The discussion continues next week.